Papers

from the 2017 CityFood Workshop

Author: James Farrer

Affiliation: Sophia University

Abstract: In post-war Japan vast black market districts surrounded urban commuter train stations with warrens of small-scale retail, food and alcohol vendors. Most were bulldozed and remade into modern shopping districts based on covered arcades and department stores. Only a few of these dense warrens of pedestrian alleyways survived into the 21st century. Recently there has been a widespread revival of these vintage market streets, but sometimes with a radically new organization of public and private space. One of the most important trends is the opening up of building fronts and the use of the alleyway, sidewalk and street corner itself as a space of eating and drinking. The movement from private and intimate indoor spaces of post-war bar culture to the street level night-market style of drinking represents several simultaneous trends. One is a challenge to the public-private divide in Japanese consumer culture, with people eating and drinking in public. Another is the transformation in the gendered culture of drinking from private male-oriented bars to mixed gendered consumer models. Finally there is the appropriation of public street space for food and alcohol consumption. At the same time, it is important that these are primarily seen as spaces for public drinking and not simply eating. Drinking in public implies an informalization, “intimization,” and sexualization of public space in Japan. The use of city space for public drinking should also be considered as an important feature of the foodscape of global cities. This paper will be based on ethnographic observations and interviews in four alleyway drinking streets in Western Tokyo.

Author: Robert Ji-Song Ku

Affiliation: SUNY Binghamton University

Abstract: Across Seoul, countless tented food stalls called pojangmacha (literally “covered wagon”) have for generations purveyed cheap, tasty fare into the wee hours of the night. The foods that typically appear under the tent are tteokbokki, sundae, odeng, gimbap, and other familiar nosh that can be washed down with beer or soju. But while these foods are as popular as ever, other sorts of gilgeori eumsik (literally “street food”) that are decidedly more “fusion” or “international” have recently competed for the ever-diminishing real estate that is legally available to street venders. One such place is Ewhayeodae Street that leads to the front gate of Ewha Women’s University. While other locations are better known for street food, this place helps us to assess two particular facets of contemporary Korea’s on-going social, cultural, and economic transformation: first, the status of women, especially young women, such as those who attend Ewha University, and second, the rise in the number of foreign tourists, especially from China. By examining this one small slice of Seoul’s expansive street food culture, this project hopes to demonstrate that the gilgeori eumsik of Ewhayeodae Street signals more than just a changing culinary taste of Korea. Rather, by offering new and innovative foods that appeal simultaneously to young Korean women and Chinese tourists, the Edae food carts anticipate an urgent social reality: As much as any other factors, the future of Seoul continues to hinge on both the ongoing evolution of the role of women and the internationalization of the country.

Author: Kathleen Dunn

Affiliation: Loyola University Chicago

Abstract: While global cities maintain elite status by attracting a transnational capital class, poor and working class immigrants play a crucial but subordinated role in sustaining these urban economies as well. This paper takes a relational view of the division of labor that produces the global city to illuminate the productive value of immigrant marginalization. Drawing on extensive fieldwork among New York City street vendors, I focus on the dialectical relationship between the conditions of low-income Latina street food vendors and those of gourmet food truck owners, a new class of native-born and highly educated entrepreneurs who have gentrified street food vending in global cities around the world. Here I focus on how the state’s production of lower-income immigrant street vending as an urban problem facilitates gentrification. I argue that the border, understood as state practices of surveillance and militarization directed at labor migrants, is a constituent element of the gentrification frontier. Latina food vendors in particular face intense criminalization, while native-born gourmet food truck owners help to resolve the ‘problem’ of the lady selling churros in the subway by innovating food vending into a practice more reflective of cosmopolitan elites. The relationship between border and frontier constitutes an increasingly important mechanism of immigrant marginalization in the global city.

Author: Edward Whittall

Affiliation: York University, Toronto

Abstract: Charting the career arc of one of Toronto’s better known street food vendors, who goes by the nom de guerre “Fidel Gastro”, this paper uses Michel de Certeau’s “strategies” and “tactics” as a starting point for thinking about street food vending as a form of street theatre, like the pop-up, site-specific performance, and radical street theatre. Doing so offers a rich critical language to describe the spatial and social interventions made by street food vendors and their customers who collude to form temporary communities in off-spaces and transitional areas of the urban landscape. I argue that these formations allow us not only to resist dominant narratives of urban order, but also to construct and perform ideals of the relationships that we desire to have with each other, the food we eat, and the city it beckons us to ingest and transform.

Author: Daniel Bender

Affiliation: University of Toronto Scarborough

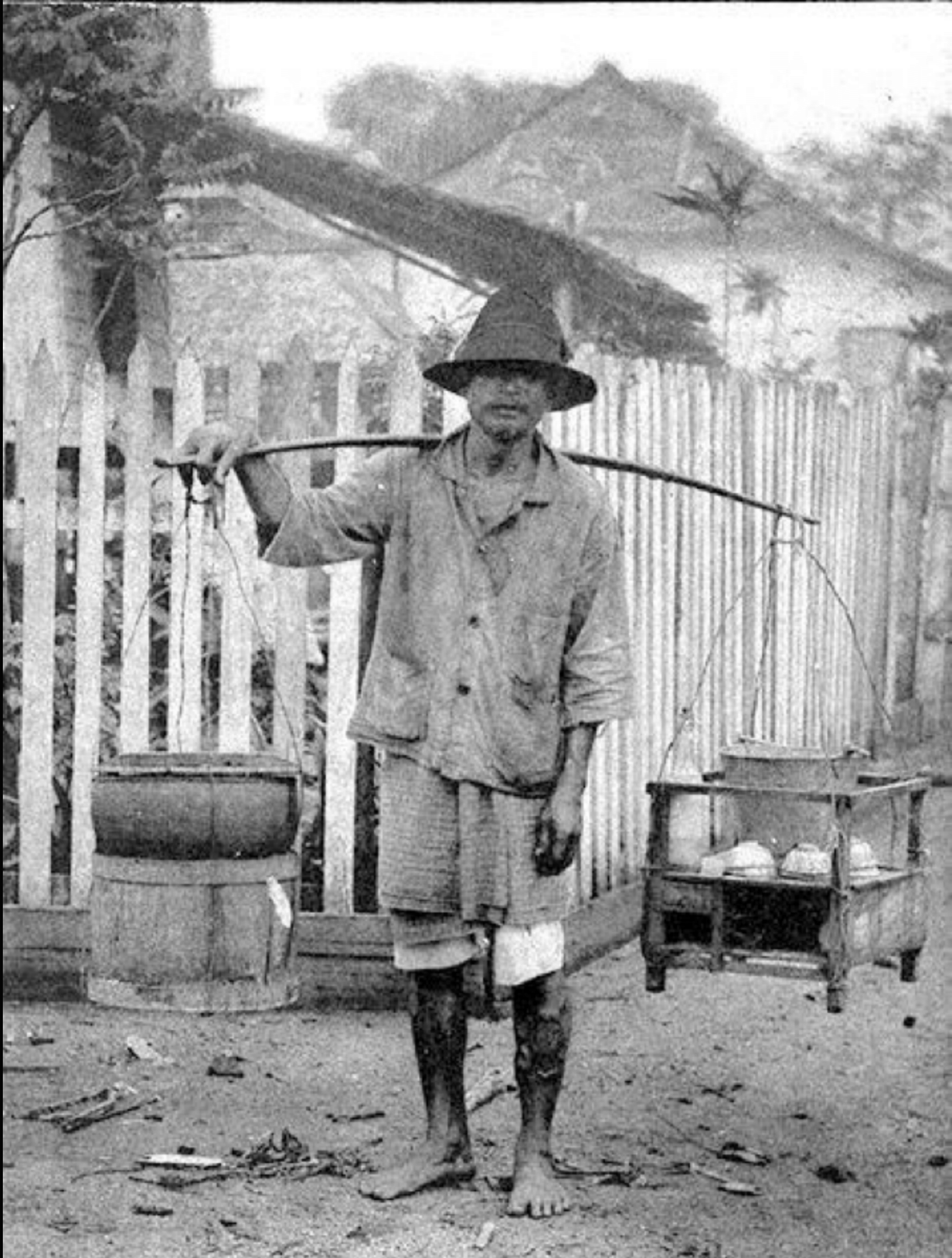

Abstract: This paper examines oral histories and visual representations of satay vendors and consumption from the colonial era to the post-colonial era. It uses these sources to understand how Singaporeans created origins myths surrounding a symbolically-important food sold by hawkers and shared across many of the island’s different religious and ethnic communities. The way they depict and recall satay vending provided a way to reflect upon the rapid urban changes of Singapore as it moved from multiethnic colony to global financial hub. Singapore once had a bustling street food culture in which the very rhythms of daily life were dictated by the passage of street vendors as they made their way around the colonial city. The movement of street vendors into covered hawker centres was a priority of the People’s Party and a critical form of social engingeering in building the multiethnic and capitalist city state. My goal is not to find the ‘true’ roots – the original satay – but to understand how the Singapore colony, then nation, depended for sustinence and pleasure on a food that was both shared across ethnic lines and a speciality of mobile peoples.

Author: Lynne Milgram

Affiliation: Ontario College of Art & Design University

Abstract: The recent Canadian Broadcasting Company article (August 16, 2016) heralding the Michelin Star awarded to a Singapore food hawker highlights the current pursuit for culinary alternatives such as street food vending and dining. Yet governments position such street activities as “illegal” privileging instead sanitized private spaces. Disrupting livelihoods that have long provisioned urbanites’ food security and work choices challenges realizing a diverse “cityness” (Robinson 2006) that can meet residents’ varied needs. This paper engages these issues by analyzing how street food vendors in Baguio, Philippines reconfigure the constraints of government street clearances to emerge as successful entrepreneurs and food innovators. I argue that to protest street vending restrictions, Baguio’s food vendors operationalize “everyday” and “advocacy” politics (Kerkvliet 2009) that materialize “gray spaces” (Yiftachel 2012) of operation and transform everyday “hunger” foods into “heritage” specialties (Van Esterik 2005) sought by consumers across classes. Some vendors banned from ambulant street sales, for example, have rented sites in a “legalized” night market and through performance-cooking – preparing meals amid flames and music – have become the market’s main attraction. Other prohibited street vendors have relocated to leased storefronts where they tailor the quotidian Philippine street snack food, suman, (rice, coconut milk and cane sugar wrapped in banana leaves) into creations that capture distinctive provincial styles, while shopping mall kiosks have usurped street-sold “native rice cakes” to offer them in “modernized” forms and settings. By refashioning street food preparation and sales, Baguio’s food vendors remain integral to the city’s street-scape. Their edgy enterprises thus problematize understanding street economies and the caché of street foods causing us to rethink what “the street” means in “street food.”

Author: Fabio Parasecoli

Affiliation: New York University

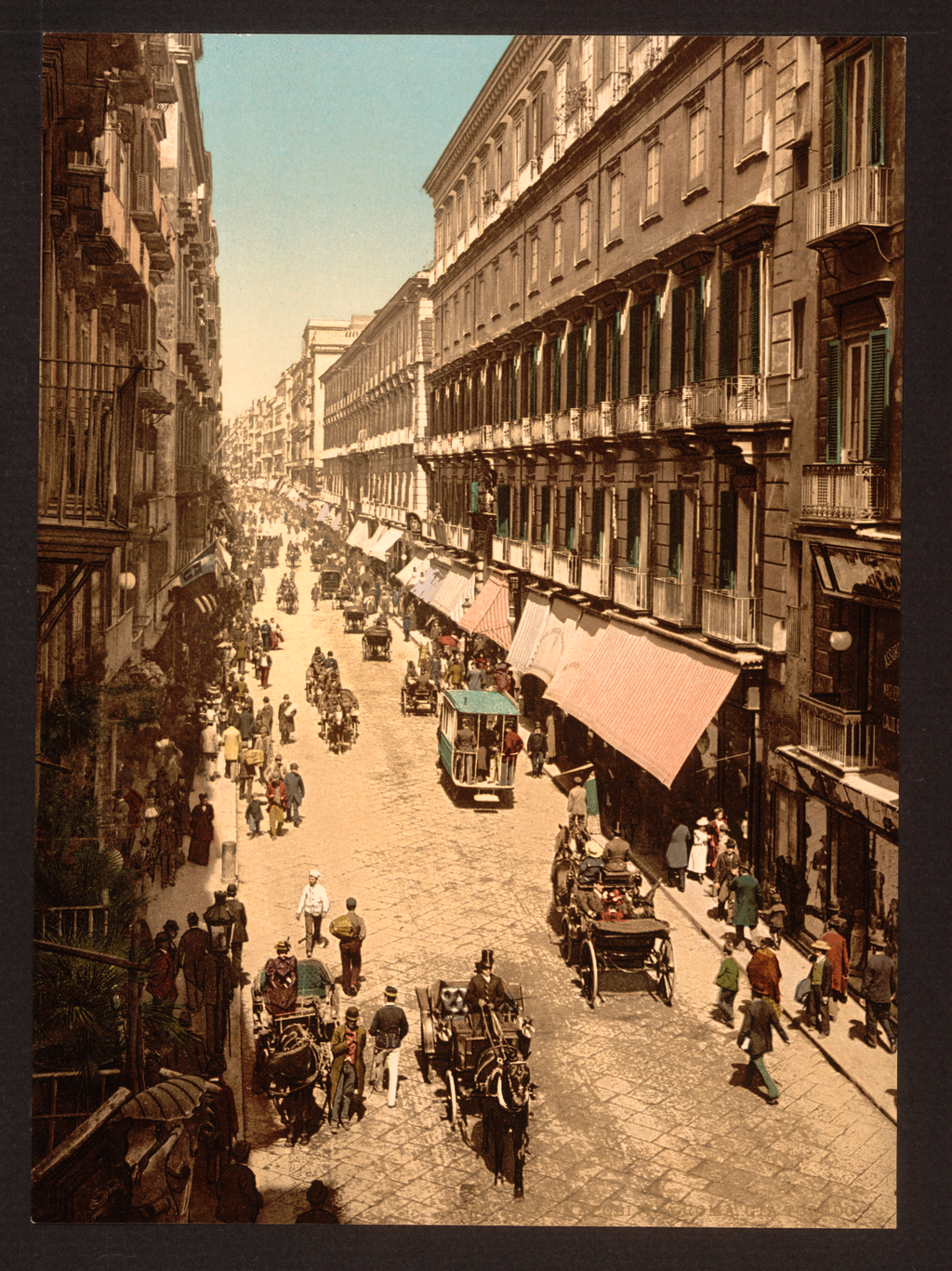

Abstract: Food has been prepared, sold and consumed on the streets of Italy and other public places for centuries, as it is the case in many other countries. In this short communication, I will outline the development of street food –cibo di strada – in Italy since the end of World War II, focusing in particular on its evolution in the past decade. Food on the street used to constitute a cheap alternative to cooking and eating at home, carrying connotations of simplicity and low social status, while elevating some specialties into expressions of communal local identities, often experienced as tradition. From the period of the economic miracle to the roaring 1980s street food almost fell into oblivion, with few exceptions cherished as almost archaeological remains. However, in recent years the reevaluation of the culinary past in all its aspects, including the humblest ones, has generated new, hip interpretations that are now in fact called “street food” in English. Many young chefs and entrepreneurs offer tongue-in-cheek versions of classics that rely on high-quality ingredients, great techniques, and well-designed presentations, from packaging to the spaces in which these foods are produced and consumed. Not only the profile of who makes street food but also the expectations and practices of consumers have profoundly changed.

Author: Jo Sharma

Affiliation: University of Toronto Scarborough

Abstract: This paper forms a preliminary stage of a project to historicize global street foods and vendors through a lens on representations and regulations. It explores imagery about street food hawkers and vendors, its production and circulation and the social and political transformations via changing technologies, urban life, consumer culture, and state policies. Examples range across Britain, the US, India, Syria, China, and Russia. The paper briefly delineates how the next stage will study such representations in the light of urban regulatory regimes on street foods. Finally, the paper discusses how the recent advent of digital archives has made it possible for scholars to explore histories of street vending in a global context, the limitations and potentials of such archives, and how the City Foods project might curate such histories more widely.

Author: Ryan Devlin

Affiliation: John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY

Abstract: Street vendors have been a part of the landscape of New York City for centuries. Despite their ubiquity and historical lineage, the right of vendors do business on the sidewalks and streets of New York is one that has been hotly contested over the years. The late twentieth century was a particularly contentious time for street vendors. Amid a broader shift toward neoliberal forms of urban governance and aggressive strategies of public space management, street vendors were targeted for strict regulation, even elimination by business and real estate interests and their allies within city government. In fact, nearly every current law regulating street vending in New York was enacted between 1977 and 2000. This paper will examine the struggle over street vending and public space during these years, paying particular attention to the ways in which vendors contested their exclusion. It will show how, drawing on decidedly liberal discourses of historical rootedness, entrepreneurialism, market competition, and fairness vendors were able to push back against attempts to regulate them out of space. Rather than put forth radical critiques of the city under capitalism, vendors utilized internal critiques of neoliberal urban policies in order to defend their place in the city. While this approach left many aspects of neoliberal ideology unchallenged, it nevertheless served as a powerful and destabilizing critique of the broader neoliberal project of urban governance.

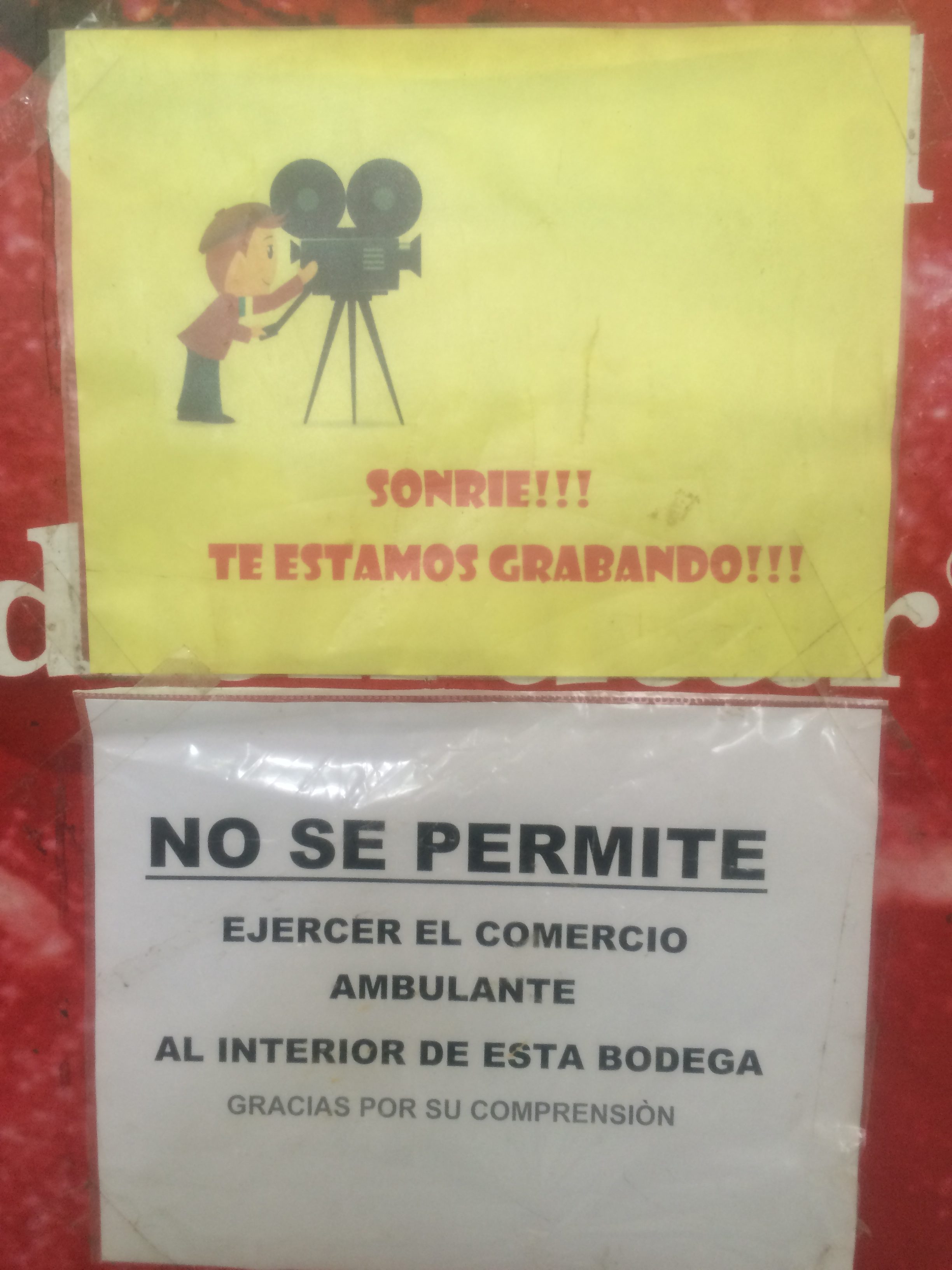

Author: Tiana Bakić Hayden

Affiliation: NYU Graduate School of Arts & Sciences

Abstract: Street vendors in Mexico City are a controversial but persistent feature of urban life, and have been subject to numerous, often contradictory, attempts at regulation by the state. These inconsistent and ultimately unsuccessful attempts have resulted, on the one hand, in the association of street vendors with corruption and lawlessness, and on the other hand in the proliferation of legal and bureaucratic mechanisms dedicated to dealing with them. This paper analyzes how this complex legal landscape appears in everyday debates over street workers’ rights in Mexico City’s largest wholesale market. I document efforts by formal merchants to lobby local authorities to remove street vendors from the market, as well as vendors’ endeavors to claims to legal recognition and their right to work in the streets. In analyzing the diversity of appeals to both legal and non-legal normative orders which these actors employ in staking their positions, I identify different temporalities and scales which they use to describe legitimate versus corrupt state interventions into street vending. Drawing attention to this ongoing tension between legitimacy/corruption, I discuss the challenges of legal regulation in the “informalized state.”

Author: Mark Vallianatos

Affiliation: Independent scholar

Abstract: Like a fluorescent tag injected into the boulevards of a transforming metropolis, street vending in Los Angeles has marked the evolution of the region and mapped out boundaries of neighborhoods, cultures and legitimacy. To contribute to understanding vending’s role in “city building” I will examine how street vending has reflected – and helped shape – changes in the demography, economy, and sense of place of the Los Angeles region.

Vending and regulation of vending were impacted as immigration from Latin America and Asia transitioned LA from the whitest big city in the United States into one of the most diverse. Food vending helped enable the rapid industrialization of L.A. during World War II and the cold war, and then adapted as heavy manufacturing declined. The fate of vending and vendors has also long been bound up in the region’s transportation patterns.

To explore these histories, I will examine the origins, development and regulation of three types of street food vending – food carts, prepared meal trucks, and ice cream trucks – in the Los Angeles region. By exploring vending’s roles in demographic change, industrialization, and transportation, I hope to help raise street vending’s profile as a building block of a metropolitan region. I also want to underscore how vending remains an active force in influencing how we use and regulate streets and public space, how low-income residents join the formal economy, and how we interact with people from different backgrounds as neighborhoods change.

Author: Noah Allison

Affiliation: The New School

Abstract: The changing nature of immigration in the United States has led scholars to recognize that immigrant settlement patterns in urban areas have become noticeably complex, finely differentiated by class, race, ethnicity, identity and interests. The city street is therefore subject to constant renegotiation amongst its residents and businesses to reestablish boundaries—both physical and metaphysical—of the local, social, economic, political, cultural and linguistic landscape. As such, “border crossing” emerges as a critical part of everyday urban experience in streets, schools, markets, restaurants, gardens, and parks, where the negotiation of space, identities, values, and rights occur through encounters with others. Identifying how and where sidewalk vendors along and near Roosevelt Avenue in Queens (re)negotiate the spaces that are not overtly public or private will add to Edward Soja’s spatial justice construct by analyzing the interplay between global and local forces and the influence of the state and its municipals. Focusing specifically on sidewalks along Roosevelt Avenue additionally illuminates what the purpose of public space is in the context of urban development, who has the legitimate right to use it, for what kind of activities, and when, providing a framework to examine the placemaking practices that immigrant sidewalk vendors play in the growth of New York City in a post-industrial economy.

Author: Amita Baviskar

Affiliation: Institute of Economic Growth, University of Delhi

Abstract: Urban order is predicated on the regulation of city spaces and the social and economic practices that animate them. Street food, like other forms of vending, disrupts and defies a modernist conception of orderly urban space and is thus frowned upon by planners, municipal officials and the bourgeois public, even as it is accommodated through an ‘informal’ cultural politics that includes complicity and corruption, tolerance and sympathy. How do street food vendors, especially migrants who cannot muster much social and economic capital, negotiate their way through an unequal city? In this paper, I use ethnographic vignettes to argue that, as much as the differences between street food vendors and other, more established, sellers of food, it is the differences between vendors that account for their heterogeneous survival strategies. These differences relate to histories of migration and ethnic identities, as well as to the variegated space of the city. Understanding and addressing the heterogeneity of urban spaces as well as street food vendors is essential for devising any policy that aims to secure their rights.

Author: Anna Greenspan

Affiliation: NYU Shagnhai

Abstract: Scholars like Ananya Roy and Jennifer Robinson have argued that there is a geographical prejudice in urban theory such that our understanding and ideas about some modern cities has become the model for all. The ‘historical experience and cultural conditions of a few ‘great’ cities,’ writes Roy, ‘have come to stand in for all conceptualizations of the urban.’ Under this theorization, Shanghai, China’s largest and most cosmopolitan city, is doomed to backwardness and can only aspire, mimic or catch up with another model of urban modernity that has already happened elsewhere.

This paper participates in a rethinking of the modern city by focusing on the contemporary metropolis of Shanghai. It does so by concentrating on street markets, street culture, street life and street food. It argues that while Shanghai’s officials and urban planners often equate urban development with ‘cleaning up the streets,’ the snacks (xiao chi 小吃) that are sold from the small shops and mobile stands – dumplings steamed in wooden baskets, nighttime barbeques, carts selling stir-fried noodles – are an integral part of the liveliness and livability of the 21st century megacity.

The paper is based on Moveable Feasts (http://www.sh-streetfood.org/) an ongoing project in the digital humanities, which aims to investigate Shanghai’s shifting street food landscape.

Moveable Feasts is a platform for experimental practices in critical cartography, which uses new digital cartographic tools to map the impermanence of the informal city. In doing so, it seeks to challenge mapping’s role as a method of authoritarian control, and use it instead as process of exploration, discovery and – hopefully – future possibility.

Author: Jackie Rohel

Affiliation: New York University

Abstract: This paper examines a contested comestible as a case study of public culture in global London.

Research has shown that one of five people in the world consumes some form of areca nut, a stimulant plant matter and key ingredient of betel quid (paan). Betel quid is a prepared comestible that is popular throughout the Indian Ocean region; it consists of betel leaf wrapped around areca nut, pickling lime and other condiments. While the extraction of psychoactive substances such as coffee and sugar linked the colonies to the European marketplace and the birth of the modern Western public, betel quid consumption was never popularized beyond Asia. As a chewed stimulant and digestive aid, it has been central to sociality in homes and on the street across Asia and, increasingly, in global cities beyond the Subcontinent. This paper examines the relationship between betel quid and public sociality on London’s streets by focusing on the vending site. For some, the making and chewing of betel quid is a social activity; it forges a local community by bringing people together in shops, in doorways and out into the sidewalk. But the public sociality – and ‘ethics of hospitality’ – enabled through communal chewing and spitting is at odds with other modern public values related to urban aesthetics, hygiene and productivity. This critical ethnography of London’s betel quid shops and their publics therefore examines dyspeptic politics in the belly of the global city. It shows how emergent concerns about toxicity and idleness, refracted through the practice of timepass, reconfigure ethnic, classed and gendered publics at these streetside stalls. In doing so, this research advances knowledge about the politics of food and civil society on the streets of globalizing cities.